The debt and deficit challenges that

drove the Eurozone to the brink in 2011 have largely faded from the news since

the restructuring of Greek debt in March 2012. However, we have continued to

monitor debt/GDP levels in the Eurozone, and specifically in the periphery

nations. In August 2012, the European Central Bank’s announced its OMT, or "Outright Monetary Transactions" program, a program that would allow it to purchase

unlimited amounts of member states’ debt in the secondary market under certain

conditions. Since the program was announced, yields on Italian and Spanish debt

have declined precipitously and, it would appear, investors have taken this as

a signal that the danger has all but past. Sadly, but not surprisingly, the

debt of the peripheral nations has largely continued to rise unabated.

Eurostat, the official statistical

agency of the European Union, recently published debt/GDP ratios for members of

the European Union. On a quarter-over-quarter basis, Europe made negligible

progress in taming its burgeoning debt as the ratio for countries sharing the

common currency declined from 95.7% in the second quarter of the year to 95.1%

at the end of the third quarter. However, we must also add that this may indeed

be due to seasonal issues. Eurozone debt/GDP bas declined in the third quarter

in nine of the last 14 years despite the steady upward trajectory of the debt

ratio. Four of the five instances in which the ratio increased in the 3rd

quarter have occurred in the last six years, yet Eurozone debt/GDP increased

24.9 percentage points from the 3rd quarter of 2008 through the 3rd

quarter of 2013. In short, the modest improvement from during the 3rd

quarter may be due to seasonal factors. With that said, charts one and two show

modest improvement for most nations.

With seasonality a potential issue, we

have looked more closely at year-over-year changes in the ratio. While this could

result in missing a turning point, reducing Europe’s debt/GDP is going to be a

very long-term process, more akin to turning an aircraft carrier than a 19 foot

ski-boat. Given significant absolute debt levels, low growth, and an inability

to devalue their currency, peripheral nations will find climbing out of their

debt overage an enormous, and indeed long-term, project. As such, missing the

exact moment when positive change occurs, if it occurs, isn’t likely to be

problematic.

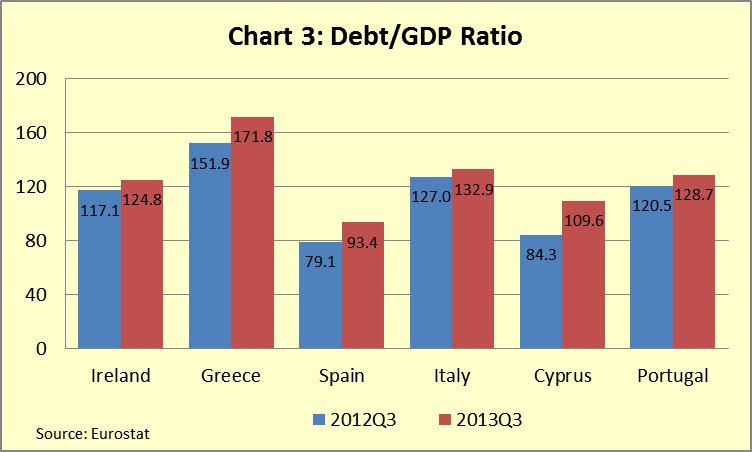

Year-over-year, Eurozone debt has grown

a relatively modest 2.7 percentage points, from 89.9% of GDP to 92.6% over the

12-months ending in September. However, for most of the periphery, debt/GDP

increased significantly. Cyprus, Greece, and Spain all experienced double-digit

increases in debt relative to the size of their economies. Ireland, Italy, and

Portugal saw smaller, albeit significant, increases in their debt ratios as

well.

Another way to look for change in the ratio is to review the slope of the debt/GDP ratio to see if it is steepening or flattening. Only in Ireland, where the ratio has essentially remained stable over the last three quarters, do we see signs of a potential peak. The modest decline in the 3rd quarter aside, the rate of change in the ratio in Portugal remains relatively constant as it does for Greece, Spain, and Italy. That of Cyprus appears to be accelerating. As such, we must conclude, that, the periphery has made little progress in reducing its debt. There have been very modest signs of growth, ECB policy has significantly lowered the cost of debt for those with market access, and others continue to receive aid. Yet for most of these countries, nominal GDP growth is likely to remain below the cost of debt over the next two years and most will continue to run primary deficits (i.e. they will run deficits before taking into account the cost of funding). As such, most will see their debt/GDP ratio continue to climb and any progress at lowering it will be very, very hard to come by, leaving them susceptible to it climbing again, and rapidly, with any exogenous shock to the economy. In short, it is far too early to suggest that these nations have put their debt troubles behind them. As we have noted before, the European debt crisis isn’t dead, it’s just hibernating.

Please note that in the chart for Greece, the brief, but sharp, decline was due to restructuring of the nation’s debt in March 2012. Despite that restructuring Greek debt/GDP reached new highs just 18 months later.